Compressors are things that many sound designers don’t understand because they don’t often obviously alter the tone of incoming audio. A filter makes an obvious change, as does a ring modulator or reverb. Compressors can be much more subtle in their sonic changes, but are important nonetheless. This article will walk through how compressors work, what types exist, and how they can be used to achieve everything from a clean mix and workable raw sounds to an interesting assortment of more designed sounds.

First, let’s talk about what a compressor even does. Generally speaking, it’s a dynamics manager, which is to say it controls the dynamic range of audio. It does so by attenuating the input signal by a set amount after a set point. that point is the threshold, and the amount is ratio. Generally speaking, compressors will attenuate the input signal that is above the threshold, to the threshold level. How close it gets to that is determined by the ratio control, and how quickly it gets to that is determined by the knee and envelope.

Now, let’s discuss the basic controls and features of a compressor. Most compressors will have some of these, some will have all of these.

-

Threshold – the level at which compression starts, usually in dB. For example, if your audio is at -6dB but your threshold is at -12dB, the upper 6dB of signal will be compressed, while the rest stays the same. Not seen on some older compressors because input gain set threshold, as threshold was set internally and the input preamp was used to bring the signal up to and past that level.

-

Ratio – the amount of compression once the threshold is reached. Generally speaking, 1:1 means no compression is applied, but 2:1 means after the threshold, the signal is attenuated 50%. 4:1, the signal is attenuated 75%, keeping the output signal closer to the threshold level. Usually past at and past 10:1 ratio you’re at brickwall territory, attenuating by 90% or more. This almost guarantees the signal is kept at the threshold level, making the waveform look straight and flat, like a brick wall or, sometimes, a sausage. Exact attenuation amounts can change between compressors.

-

Attack/Release – rate at which the compressor lowers or restores volume by approximately 2/3 of the threshold. Sometimes just a “time” control or nonexistent. There’s no standard for this, so even if you see a specific time listed, like 20ms, it may not exactly correspond with the actual amount of time it takes to change. It’s worth noting compressors will start compressing the instant the threshold is reached, so this isn’t like a delay or fade of how quickly the compressor reacts.

-

Auto – usually implemented as a dual envelope system, auto attack/release tends to just use 2 speeds at once, one faster, and one slower, to catch transients as well as smooth out a signal.

-

Knee – refers to the “softness” of the compression, or how gradually it compresses. A hard knee will not affect the audio at all until the threshold is hit, at which point it immediately beings compressing. A soft knee will smooth out that transition, so as you approach the threshold, it begins to compress slightly.

-

Makeup Gain – amplification after the compression stage. As compression can result in a quiet signal, this helps bring it back up to what it was before. This is often what makes people think compressors make things louder, when in reality it’s the reduction of dynamic range and bringing volume back up that makes it be perceived as louder. Makeup gain is sometimes an automatic function.

-

Lookahead – delays the input audio before the VCA but after the envelope follower by a few milliseconds. This is so that even the fastest and harshest transients can be caught, because the gain reduction element will be reacting before the audio actually reaches it.

-

Sidechain – On a basic level, compressors use an envelope follower to derive the amplitude information of input audio. that is then processed by logical processors and slew limiters to set threshold, ratio, attack, release, and knee. Sidechain, or keying/ducking, allows you to use an external signal as the envelope follower’s source, meaning the input audio is compressed based on the sidechain audio. The most typical use for this is making one sound quieter when another sounds, such as chords being attenuated when a kick drum plays. It’s also useful for making background music quieter when a narrator is speaking.

-

Peak/RMS – Peak compression is what most people think of: the compressor compresses when a peak, like the transient of a kick drum, goes beyond the threshold. However, RMS, or root mean square, compression determines the average volume of input audio and compresses audio to meet that average. In practise, this basically means a low threshold will have a lower output, but dynamic range will largely be preserved.

If you’re more image-focused, this diagram should be of use:

That’s the block diagram for a feed forward compressor. Feed back compressors also exist, which takes the sidechain/audio signal for the envelope follower after the VCA. Speaking of which, let’s discuss types of compressor:

-

FET – most notably, the 1176, these use a field-effect transistor as the gain reduction element. It has a relatively fast reaction speed with subtle colouring, making it a popular choice for many things.

-

VCA – most-used, especially in more budget compressors, these use a VCA, often an OTA-based VCA, as the gain reduction element, like in a synthesizer. VCAs are very fast and don’t usually add much colour.

-

Tube – most notably, the Manley Vari-Mu, these compressors make use of a vacuum tube as the gain reduction element. They are relatively slow to react and heavily colour the sound, giving them a distinct tone.

-

Opto – most notably, the LA-2A, these use a vactrol, or photoresistor with a light, as the gain reduction element. Vactrols are very slow to react but also do not colour sound much.

-

RMS/Peak – as discussed above, but including here because some compressors don’t have the option to switch, and it’s good to know what kind of compressor you have. Usually tube and opto compressors are RMS, whereas VCA and FET are peak, but this can vary.

-

Feed forward/back – also as discussed above, but it’s worth noting this is usually fixed. There’s not a large difference between the two in use, but technically speaking feed back compressors will have lower maximum ratios and lower dynamic range to work with because they take the envelope after it’s been attenuated.

-

Multiband – basically, multiple compressors applied to different parts of the frequency spectrum.

-

Dynamic EQ – like a multiband compressor and EQ combined, but can also have negative ratio, which increases output volume instead of decreasing it.

-

Expander – opposite of a compressor. It makes things above the threshold louder, also known as negative ratio. Often built into budget compressors along with a gate function.

-

Upwards compression – Not to be confused with an expander, upwards compression is usually built into multiband compressors, and is useful for bringing quiet sounds up in volume while retaining dynamic range of louder parts. Using this with normal or downwards compression allows you to create very undynamic sounds.

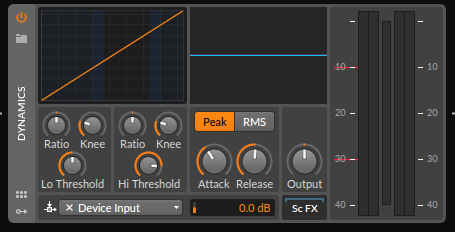

OK, now that I’ve blabbered on about all the idiosyncrasies of compressors on a technical level, let’s talk about actually using them. The most important thing to note is that most any type of compressor can be used for most any compression task. The main difference will be the tone of the output sound, and how well it handles sharp transients. I tend to prefer VCA-based feed forward compressors that work based on peaks with a hard knee and lookahead, just because they tend to be the most versatile. For the longest time, I specifically used an Alesis 3630 with a few modifications, which has all of that except lookahead, which I could emulate using a fast delay and the sidechain input. Now I use a compressor of my own design, or software compressors, usually Bitwig’s Dynamics plugin:

Typically, compressors are used to reduce dynamic range. For example with a vocal performance, you often use compressors as part of the input signal chain to reduce the overall dynamic range, as vocals can vary greatly in volume. A controlled dynamic range means audio will perform more regularly to any post processing, especially saturation, and will help make processes like EQing easier as cuts or boosts will have less dynamic effects. I regularly use compressors on my modular synthesizer’s output because, being a bunch of irrelevant circuits being interconnected, highly dynamic changes can occur nearly instantaneously. For this case, you’ll want a peak compressor with moderate threshold and ratio, but fast attack and moderate release.

Compression is also useful for mixing several audio sources together, because the more regular the dynamics are, the easier it is to set volume levels to create a cohesive mix. Compressors are used in the mastering stage of audio work, mostly in music, as a way to “glue” the mix together (you may have heard of a glue compressor, or even used a plugin called such). These are used with moderate settings to high across the board, so a high-ish threshold, low ratio, and long envelope times, often employing RMS compression and slower responding cores, like tube or opto.

Some neat uses for compressors include fast envelope distortion, where you distort the sound by using low threshold, high ratio, and fast envelopes, such that the compressor can react to changes within single cycles of audio. You also have parallel and series compression, which refers to 2 compressors in different configurations to process audio differently. Series is useful for mastering, as you can catch any transient peaks as well as level the audio, such as with the Shadow Hills Mastering Compressor, whereas parallel is useful for creating upwards compression when you don’t have an upwards compressor. It works by reducing dynamic range then amplifying, then mixing with the unprocessed signal. it effectively increases the volume of quieter signals while retaining dynamics of the louder parts.

Transient shaping and changing length of sounds (aka, adding sustain) is another use for compressors. Most people use a dedicated transient shaper for this, but you can use any standard compressor for it too: increasing attack time means transients will pass easier, making the attack of any sound seem louder. Pumping can be achieved with a low threshold and high ratio, so the attack is more pronounced. Sustain employs a long release time and makeup gain to make sounds seem to last longer, as the tail is amplified and “sustained” at a set level longer.

Bus compression, or compressing multiple tracks mixed together, is useful for creating a cohesive mix of a certain element, such as a drum set or multiple guitars playing similar things, or multiple vocalists performing similarly. Also, within a modular environment like what I tend to do sound design in, you can use an envelope follower into an inverter to control a VCA as a makeshift and very crude compressor.

Bear in mind, despite just giving some general settings you can use for different effects, there’s no catch all setting that you should always use, because the same settings will have different effects on different sounds. Some things are always true, however:

-

Faster envelope times will often introduce artifacts or pumping depending on how fast the compressor core can react.

-

Longer envelope times allow it to act more as a levelling amplifier.

-

Moderate envelope settings let compressors catch transients more effectively and retain dynamics.

-

Lower threshold and higher ratio means the compressor will react more aggressively.

-

Higher threshold and lower ratio means the compressor will react less aggressively.

So, that’s more or less everything I know about compression and its use. I may add to this article as I think of or learn more things, but this should give you a general idea of what compressors are, how they work, and how to use them. As with more things, it’s important to experiment, and use an oscilloscope if you have to to see what the compressor is doing to your audio.

Leave a comment